A rent non-payment letter received from a Tenant is not unexpected. Many hundreds of thousands of commercial tenants across the Country are sending similar letters to Landlords (indeed, some national Tenants are sending a ‘template’ to ALL their Landlords), because the Tenants’ customers are not showing up; the customers are Sheltering-in-Place (SIP).

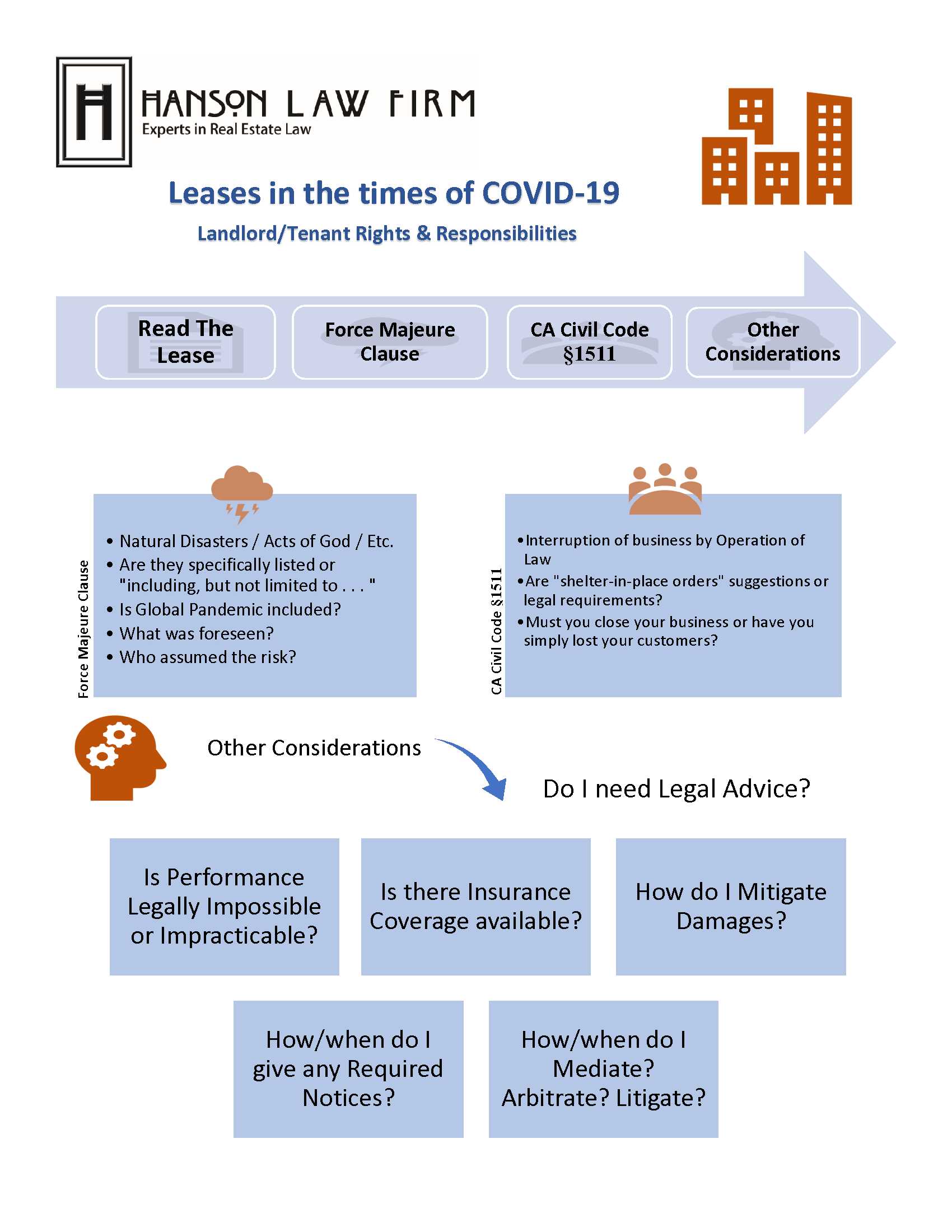

The situation Landlords and Tenants are in now is generally covered by one (or more) of three legal doctrines:

I. Force Majeure

II. Impossibility / Illegality of Performance

III. Frustration of Purpose

We’ll address each of them in order, as they are likely to apply in California.

I. Force Majeure

A “Force Majeure” clause in a lease stands for the proposition that the Tenant’s obligations to pay rent (or do anything else under the Lease) is excused when a “force majeure” (often thought of as an “Act of God”) interrupts that performance.

At its nub, a force majeure clause is all about allocation of risk. The “risk” is that the cash flow received by a Tenant from its customers and then paid to a Landlord is interrupted by an unexpected event.

Generally, a “force majeure” event is a natural occurrence (flood, earthquake, fire, hurricane) or some other “natural phenomena.” The force majeure clause identifies which specific force majeure events will excuse a Tenant’s obligation to pay rent.

Most leases have a “force majeure” clause. Most, but not all.

If the Lease has a force majeure clause, it will – again typically – list the forces majeure that the clause applies to – – e.g. “flood, earthquake, fire” etc. This becomes important because, if the triggering event that is later claimed as a “force majeure” event is not on the list, the Tenant does NOT escape liability for non-performance. By listing some forces majeure, the Tenant is often deemed to limit or “close” the list of force majeure events to those things listed, and only those things. It is presumed that the Tenant thought about and protected against only certain risks. Having done so, any other risk is presumed to have been accepted by the Tenant.

I say “often” because California, unlike, say New York, allows some flexibility in the determination of what is a force majeure – even if such an event is not listed in a force majeure clause, if the event is “unforeseeable at the time of contracting.”

How much flexibility? That is what the courts over the next two years will be determining.

(I know, that’s not a helpful answer…)

Two California statutes will also have some interplay in determination of a “force majeure” claim by a Tenant. The first is California Civil Code § 3526.

“No [wo]man is responsible for that which no [wo]man can control.”

The second, and more applicable, is California Civil Code § 1511, which states:

“The want of performance of an obligation, or of an offer of performance, in whole or in part, or any delay therein, is excused by the following causes, to the extent they operate:

“(1) When such performance or offer is prevented or delayed by the act of the creditor, or by the operation of law, even though there may have been a stipulation that this shall not be an excuse; however, the parties may expressly require in a contract that the party relying on the provisions of this paragraph give written notice to the other party or parties, within a reasonable time after the occurrence of the event excusing performance, of an intention to claim an extension of time or of an indication to bring suit or of any other similar related intent, provided the requirement of such notice is reasonable and just;

(2) When it is prevented or delayed by an irresistible, superhuman cause, or by the act of public enemies of this state or of the United States, unless the parties express to the contrary; or,

(3) When the debtor is induced not to make it, by an act of the creditor intended or naturally tending to have that effect, done at or before the time at which such performance or offer may be made, and not rescinded before that time.”

IF the Lease has a force Majeure clause, and IF that clause lists “pandemic” or “viral contamination” it’s a pretty closed case in terms of the question of whether the Tenant has an obligation to continue to pay rent. The answer would be “no.” At least, for the duration of the pandemic.

But, the “pandemic” must be the proximate cause of the non-performance. As of April 1, it could be argued that the customers of the Tenant have not yet been determined to suffer from the

pandemic, so there is no “cause” attributable to it that offsets the Tenant’s obligation to pay rent.

—–

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD FULL WHITEPAPER

—–

In most cases, right now anyway, the performance of the Tenant is impaired by voluntary human behavior. It’s clients and customers are voluntarily staying away. This may not qualify as a “force majeure” event.

While non-performance because of “governmental order” isn’t an “act of God” – it may be listed in a force majeure clause nonetheless.

What may (and likely would) qualify as a force majeure event is a “governmental order” mandating that the Tenant’s customers “stay away” from the Tenant, whether listed in a force majeure clause or not.

Of course any likely governmental order is not going to be to specific customers of a specific type Tenant. The order would likely be broader than that, and be an order for “people” (i.e. a Tenant’s customers) to “shelter in place” – – – and possibly mandate the closure of health clubs or bars or nearly everything else. Or the order may require specific types of Tenants to cease their operations.

The key is the gravamen of the governmental action. Is it an order, or a suggestion?

No case has yet decided that question.

Which leads to the next consideration: What if the force majeure clause says something like “including but not limited to, fires, floods, earthquakes” or “or other perils” ?

Some Leases might define a “Casualty” as “fire, explosion, flood, earthquake or other peril.” The Lease might state that in the event of a “Casualty” to the property, rent is abated.

What is a “peril”? Suppose the Lease does not define “peril.”

As used in the insurance industry a “peril” is a specific cause of damage or injury to a piece of property or person. Insurance against perils is different from, and in addition to, liability protection.

Nearly every insurance policy protects against multiple perils, but some insurance policies only cover specifically named perils on their policies. This is called named-peril coverage, also known as closed-peril insurance, specified-perils insurance or a named-risk policy. Meanwhile, a policy that will reimburse for all causes of damage besides specific exceptions is called all-peril coverage. This type of coverage is sometimes referred to as open-peril, special-perils or all-risks coverage.

In most common insurance policies, the real property structure and personal property are insured differently. The structure is protected against open perils, while personal property is only covered from things specifically described in your policy.

In colloquial English, the words peril, hazard and risk all have similar meanings and can sometimes be used interchangeably. But when it comes to insurance, they have very specific (and different) definitions that relate to one another. Consider this example:

“The low-hanging brush increased the risk of a wildfire destroying the property.”

In this scenario, the wildfire is an example of a peril: something that can damage property. And the low-hanging brush is a hazard: it increases the likelihood that a peril will cause damage to the property. Risk describes the likelihood that a specific peril, or perils overall, will cause damage to you or your property.

Sometimes, the phrase hazard insurance can be used to describe the portion of an insurance policy that covers your property dwelling from perils.

Perils Commonly Covered By Insurance

There are 16 basic peril types that are commonly covered by a “named perils” insurance policy. However, this isn’t a universal list. Exactly what is or isn’t covered in a policy can vary based on the insurance company, the property location and the type of insurance policy bought, so it’s essential you read the policy in detail to know what it covers.

They are sometimes called “perils insured against,” which can usually be found in the “Perils Insured Against” section of the policy. If there is an open perils policy, no perils would be listed; only exceptions.

A typical list of Insurance perils includes:

- Fire/lightning Windstorm/hail Explosion Riot/civil commotion

- Aircraft Vehicles Smoke Vandalism/malicious mischief

- Theft Falling objects Weight of ice, snow, sleet

- Accidental discharge/overflow of water or steam

- Sudden tearing apart, cracking or bulging (in water/air systems)

- Freezing Damage from electrical current Volcanic eruption

Insurance policies always name specific exceptions to a policy—perils that are not covered. As with covered perils, things that aren’t covered will vary by insurer and where the property is, but many named exceptions are common across all insurers.

Additionally, you can protect yourself against some perils, like flooding, by purchasing a rider, endorsement or supplementary policy. For example, you can buy catastrophe insurance or “cat perils,” which includes protection from windstorms, floods and earthquakes. But other exceptions, like neglect, can’t be covered by insurance at all.

A typical list of Excluded Insurance perils includes:

- Ordinance/law Earth movement Water (flood, sewer backup)

- Power failure Neglect War

- Nuclear hazard Intentional loss Governmental hazard

So, if the definition of “peril” is that used in the insurance contest, “governmental action” is NOT a “peril” which could be used to excuse a Tenant’s obligation to pay rent under a force majeure clause.

It is important to note that “perils” apply, most often, to “property” damage – not to income interruption.

It is also important to note that – if “other perils” (or words to the like) are used, the Tenant must demonstrate that public health hazards were – at the time the Lease was drafted – intended to be covered by that “peril” language. Hindsight (or revisionist memory) will not allow a Tenant to re-interpret the term to cover an epidemic if that was not contemplated at the time of drafting the Lease.

It is also important to note that, when the purpose of the Lease has not been totally destroyed, mere impairment of a Tenant’s cash flow is NOT a good enough reason for relief under a force majeure clause. Nor does fear of commercial loss.

II. Impossibility / Illegality of Performance

Impossibility and/or Frustration of Purpose require: a) an unforeseeable event, that is b) outside the parties control and c) renders performance impossible or impracticable. After all, as CA Civil Code § 1441 states:

“ A condition in a contract, the fulfillment of which is impossible or unlawful …, or which is repugnant to the nature of the interest created by the contract, is void.”

Thus, in addition to the “force majeure” clause in the Lease itself, and CA Civil Code § 1441, there are also other statutory protections a Tenant may avail themselves of – if certain criteria are met. CA Civil Code § 1511 (which is a codification of the “force majeure” doctrine) states that the “operation of law” may prevent or delay a Tenant’s performance under a Lease; as may an “irresistible superhuman” cause or event.

However, the cause must apply to the Tenant. Where a Tenant has made a promise to pay rent, and that payment cannot be made without the co-operation of the Tenant’s customers (for instance, in a gym or workout facility, those third party persons who must come and pay to use the facility generating income for the Tenant), the Tenant’s obligation to pay rent is NOT excused because of the non-cooperation or use of those “third-party” customers.

Laws or other governmental acts that make performance unprofitable or more difficult or expensive do NOT excuse the duty to perform the contract.

“Impossibility” must relate to the “thing to be done” and not the inability of the obligor to do it. If performance is not inherently impossible, non-performance is a breach – even though the cause is beyond the Tenant’s control, since the Tenant might have provided against them in the Lease. The Tenant must show that “extreme and unreasonable difficulty, expense, injury or loss [is] involved.

If there is a legal “impossibility,” the excuse for performance exists only as long as the impossibility. However, “impossibility” may exist if it is so difficult and expensive to perform that it is “impracticable.”

But what about that “irresistible superhuman” cause? Is a pandemic / virus such a thing?

In the case of a storm that could not have been reasonably anticipated, “superhuman” cause was NOT found. The “exculpatory rule applies only when human agency does not participate in proximately causing the harm.”

Is the spread of the virus caused by “human agency” which triggers a governmental order? If so, “impossibility” may not provide excuse for a Tenants non-payment of rent.

III. Frustration of Purpose

The third doctrine, akin to Impossibility, is – Frustration of Purpose.

Frustration can be invoked when official governmental action prevents the Tenant from using the property for the primary purpose for which it was leased. However, in order for the defense of commercial frustration to apply, the “desired object” of the contract of BOTH parties must be frustrated.

An inquiry must be made, then, as to whether the Tenant’s purpose (to collect income from its customers) is the same as the Landlord’s “purpose” – to collect rent from the Tenant; after all, the Landlord is not a partner or co-venturer in the Tenant’s business. Indeed, the obligation to pay rent is not dependent upon the Tenant’s success as a business; the obligation would exist if the Tenant was simply poorly run and failed to generate enough revenue from sales.

With regard to frustration invoked by “operation of law” – it is important to note that when a Tenant’s business is NOT made “impossible” or “illegal” but is merely restricted, and where government regulation did not entirely prohibit the business to be carried on, but only limited or restricted it – thereby making it less profitable, the Tenant is NOT excused from payment of rent. So, if – for instance – the Tenant is a fitness center, even a restriction limiting the number of persons allowed onto the premises might not constitute sufficient “governmental action” to meet “frustration” purposes if the Tenant can still – for instance – hold fitness activities “on-line.”

Governmental action that makes performance of a contract unprofitable to the Tenant, more difficult, or more expensive, does NOT excuse the duty of the Tenant to pay rent.

Yet, if the governmental action makes it “impossible” for the Tenant to perform, the obligation to pay rent is excused.

ANALYSIS STEPS

So, of the many steps in an analysis of the situation, the first one is READ THE LEASE:

1) Determine if there is a “Force Majeure Clause in the Lease.

2) Determine what constitutes a “force majeure” event.

The next thing to be cognizant of is:

3) The NOTICE PROVISIONS in the Lease, and how any notice is stated.

Some Notices can be drafted by the Tenant (intentionally or otherwise) in a way that acts as an “anticipatory repudiation” of the Lease – i.e. a breach of the Lease by the Tenant and an effort to terminate the Lease agreement.

How a Notice is interpreted is important for several reasons, not the least of which are the presence of a Tenant in a Lease the Landlord would like to get back from the Tenant; or a Lease in which the Landlord very much wants to keep the Tenant in place. Depending on the motivations of the Landlord and Tenant, how the “Notice” might be construed is a critical concern. All Notices must be carefully written to eliminate unintended consequences.

Once the analysis of “force majeure” is complete, then also consider the alternatives to performance:

4) IMPOSSIBILITY / ILLEGALITY

5) FRUSTRATION OF PURPOSE

After determining if there is an excuse to the Tenant’s performance, the next thing to consider is:

6) INSURANCE

The principle type of insurance that might apply to this situation is what’s known as Business Interruption insurance.

Of the commercial policies a Tenant (or Landlord) is likely to have, a Commercial General Liability (CGL) is the one each should look to at first.

A typical CGL policy is an ISO policy (one written by an insurance trade association – the Insurance Services Office – and regularly used as a template for language related to coverage). Most ISO policies cover only damage to property – only the physical property. Does the virus affect “property”? – No. Thus there is likely no coverage.

Rental loss (from a Landlord’s perspective) or income (from a Tenant’s) is generally NOT covered by an ISO CGL policy – unless that rental loss is attributable to “property” damage.

Even if there is some opportunity to make an argument for coverage under the initial terms of the policy, it is important to review the separate “exclusions” from coverage. Almost all ISO policies exclude coverage related to “viruses.” It is important not to confuse a “virus” with “mold” or “bacteria.”

Some CGL policies are “custom” or “manuscript” policies. These are not ISO policies and the terms of coverage are crafted for each unique policy, which will require careful scrutiny so see just what a covered loss (or peril) might be.

One area of confusion will no doubt be the difference in effect of a “force majeure” clause in a Lease and that contained in any insurance policy. For instance, if the force majeure clause in the Lease binds the Tenant to payment, the same or similar clause may relieve an insurer from payment of any claim by the Tenant for the liability of that rent payment.

CGL policies are not the only insurance coverages to review before this analysis is complete. Umbrella policies, or specific rental loss policies may apply. Read all of them.

In any breach of contract, the parties are required to mitigate the damage caused by the breach. Thus, careful consideration of:

7) MITIGATION EFFORTS

is the next step in any analysis. Has the Tenant (in the example of a fitness center) transitioned to “on-line” classes? If the Tenant is a “club” is it still collecting dues from its Members? Are those revenues being used to pay other expenses than rent? If so, why? Has the Tenant cut staffing and reduced operating expenses other than rent? If not, why not?

A Tenant attempting to invoke a force majeure defense to payment of rent must show it has made “sufficient” or “reasonable” efforts to avoid the consequences of the force majeure event.

After careful analysis of these (and likely additional) factors, will a Landlord and/or Tenant have better footing from which to approach what will be a most difficult discussion.

If there is going to be a dispute, how best to approach it?

8) LITIGATION OR ARBITRATION – NOW?

Some have posited that when the question of the obligation to pay – or even the continued existence of the Lease itself (in the case of an “anticipatory breach”) – is at stake, it is better to be proactive and bring suit for Declaratory Relief – now. Why “now”? Because the courts are also impacted by the COVID 19 closures of the judicial offices throughout the state. Filing suit now, at least allows a Landlord or Tenant to get a place near “the front of the line” for dispute resolution when the courts reopen. Declaratory Relief actions get precedence over some civil claims, and when the monetary impact means the difference of keeping a business open (for either the Landlord or the Tenant!) or going out of business completely, speed is critical.

As an alternative, if the Landlord and Tenant can’t reach a pre-dispute resolution to the problem, they may voluntarily (or mandatorily – if set forth in the Lease) engage in a mediation effort or arbitration proceeding. Private mediators and arbitrators are not as impacted as the court system, and “speed” is more likely available in those forums.

—–

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD FULL WHITEPAPER

—–

As is true in every situation where someone seeks legal advice, each case is different. Each case is dependent upon the unique facts attributable to it.

This Memo is not, and should not be construed to be, legal advice. It is the writer’s summary of the legal principles which might apply to this “novel” Corona Virus situation.

If you believe you are in a situation where legal advice or assistance is needed, feel free to contact the firm, and set up an appointment with one of our attorneys. We’ll be happy to help where/when/if we can.

CDNH

HansonLawFirm.com

ContactUs@HansonLawFirm.com

877-411-9181